Working for film industry being a challenge in our society, how was the progress with Hashmi Media Institute, Karachi and Department of Film and Television (NCA) been?

Wajiha Rizvi: “Well! It’s been an interesting experience all the way through. It’s not just about the film industry, but the concept of workingwoman is still very challenging in our society. People have difficulty coping with the individuality, independence, and financial power of working women unless she surrenders before the superiority of the man and allied forces.You know what I mean. But, I feel privileged that I had the sheer support from my family and hubby for my work. In fact, he has been to most of my workplaces, sometimes just to pick and drop when it was needed, and sometimes just to socialize. Many of my colleagues, friends, and students knew him as a jolly person. Some specially had great regard for my mother, her unlimited hospitality and love they all could feel. My father still asks about my friends if he learns someone is visiting Lahore after so many years, decades actually. My mother took great pride in all of my successes till she lived. Be that for my semester result as a graphic design student at NCA in the eighties, or my diversion to film and TV within initial years of working in the advertising industry as I was awarded four scholarships, including Fulbright, FCOSAS, Chevening, and GIMD for higher studies and professional development from abroad. If you believe in the imaginary (o’haam) and power of a mother’s prayers and support that you feel and breathe for years even after her, lack of funds and resources was never a hurdle in my way. The nature paved paths to every milestone I imagined.

Now coming back to your question… Professor Sajida Haider Vandal, Principal, invited me to set up a department of film and television at NCA while I was shooting SAF Stars Quiz Show to raise funds for the 9th SAF Games in Islamabad and then boss Syed Mahmood Hashmi invited me to plan and establish the Institute in Karachi. Thankfully, both of the wise people were exceptionally supportive. If you ask me the meaning of “Vandal”, I would say it means “a clear path” if you are honest and committed to delivery. She with her unlimited vision, (jisay kehtay hain na beda uthaya), initiated the work to set up a number of new departments at NCA and make it a university. As you know all of her proposals were approved and many new departments emerged at NCA. Just the last bit is taking time to materialize. It may be due to the gap that may be her absence created as NCA has seen lots of instability and poor focus in recent years. So, I wrote the curriculum proposal and the PC-1 proposal for the release of funds from the HEC. I set up the studio, bought books, hired faculty, and enrolled two batches of students under her supervision. You know the rest of the story. It’s just happening.”

Can you give us more insight into your work as Director of Film Museum Society?

WR: “We established the Film Museum Society with zero resources in 2007 as I wished to do something that I had proposed to the Principal-NCA in 2004. I proposed to Professor Sajida Haider Vandal that we start collecting film archives and conducting film research three years ahead of time as we will be teaching history and theory of Pakistani film to the first batch of students to be enrolled in the bachelors of film and television program as part of a compulsory course by 2007. She said, “It’s a tedious job. First set up the department and initiate the degree program; then hire two assistants and do this job.” So, I began the work myself after becoming a Fulbright alumni. I have a personal collection of 9000 film archives starting the pre-Partition era and write about films. I do a mix of different things from producing to teaching film production and research, and related consultancy for institutional setting up or design courses. We just participated in updating grade-1 curricula for Punjab, perhaps after three decades.”

You recently presented a very interesting comparison of various depictions of women in local films through your paper called “Visual Pleasure in Pakistani Cinema”. Can you elaborate?

WR: “Well! Where are you getting all this information? The paper focuses on the change in female representations over a period of time. The early Pakistani films promoted the chhooi-mooi girls who were trained to not raise their eyes before the elderly and men as opposed to the sexually expressive bold and beautiful women of the post-Zia era. I mean, you can say the paper compares the filmic images of women before and after the issuance of Motion Picture Ordinance (1979) and the Censorship of Film Rules (1980). It’s a comment on the ethics and mores of one society and the implementation of one set of morals or rules in different eras.”

You presented another paper on the Decline of Pakistani Cinema in 2010. What do you think are the reasons for this decline?

WR: “Hmmm! The paper is a comment on the political economy of the film. It discusses the progress of Pakistani film under different political regimes. The decades reflect a cinema that has survived without the state sponsorship for the infrastructure, training opportunities, technology advancement and funds for over half a century.

If you go through the history of Pakistani films, the first one thousand post-Partition films were produced in about 25 years by 1972, the second during Bhutto-Zia regimes by 1983, the third during Zia-Bhutto regimes by 1994, and the fourth has taken so much time like the early years of Pakistan.

During General Ayub’s martial law regime, the average annual film production rate increased from approximately 11 to 48 per year. I mean our target was thirty three films when he began in 1958 and a hundred when he was pushed away in 1969.”

Ironically, the highest numbers of annual films, about a 100 per year, were produced during the martial law regime of a legally declared traitor, General Yahya Khan and the postwar period of the executed President cum Prime Minister, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Despite the prisoners of war (POW) crisis of 1971-72, the average annual film production rate sustained at 114 films till his demise. Musharraf’s media expansion and the continuation of the negligent “no state sponsorship for film” policy nearly duplicated 1960s figures in the new millennium. The state sponsorship was most needed at the time of media expansion, or at least Musharraf and his successors should have focused on alternate methods to improve film finance. I mean, money, money, and money. Its lack tears the smallest family units while we are talking about an industry. At least acknowledge that it is an industry that needs the infrastructure, technology, trained people, and funds whether through state sponsorship or alternate means. At least be serious and facilitate the process of revival.”

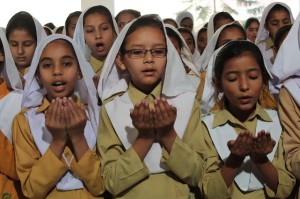

Your latest documentary Pakistan: Education and Women addresses the issue through human stories of the subjects. How was this experience?

WR: “People… It’s amazing to be able to talk to real people and listen to their stories. I am really glad I could expand the Lahore project to other provinces. It feels like a dream trip to Manchhar Lake and Kando Bozdar in the interior Sindh and Maira Kachori in KP. We also have the footage from Qila Hizabzai and Quetta. We experienced consistency in public opinion, despite culturally rich provincial images. We loved to see the kids play and sing and women laugh at these places. I felt happy and sad when one man out of a few men and women sitting on one charpai at Manchhar Lake said, “He is illiterate, but his grandfather was a literate person and he is happy that now his grandchildren are studying.” I felt happy and sad because Sindh Education Foundation provided them a school after a gap of three illiterate generations from his father to his son. I felt sad knowing that their culture: so many men and women sitting together and on one charpai will disappear whenever they get their basic right to facilities of life. After talking to people in so many places, especially Maira Kachori, I agree with Professor Anita Ghulam Ali that it is largely the economics of education that affects access and parity for females in Pakistan.”

Being an educationalist, what are your views regarding the current status and national policies of education in Pakistan?

WR: “Education for All through “access, access, and access” is my only view. You got to provide free and compulsory education to all and devise a system of accountability for whoever comes in its way. Be that parent, or landlord, or the local politician. You got to take care of the prerequisites besides providing just the buildings or budgets for teachers’ salaries. The target should be “no cost to parents or guardians” and shall also devise a system of free and safe transport to and from schools throughout Pakistan. I mean we got to move beyond creating expertise to create bundles of paperwork.”

Do you have an optimistic outlook for the revival of Pakistani Cinema?

WR: “Yes, I have. Thanks to the media expansion, academia has turned its attention to film and video production and research. Many young students and graduates who are producing, participating, and winning international awards and recognition for their very first 2004 film until now will eventually produce great feature films and revive Pakistani cinema. Their films are short, sometimes very short films at present, but their variety of themes bear what’s needed for Pakistan. These young filmmakers will eventually give a U-turn to the decline. In my view, most of Pakistan (perhaps also the government) does not know that these young filmmakers are continuously winning prizes for their very low budget short films from the North to the South of the globe since 2004. Most of them have graduated from the state institutions. Also, the international community has diverted its attention through media funding to Pakistan. These factors will have their impact.”

What motivated you to work in this field and on these particular issues?

WR: “Truly speaking, I don’t know. I think I am used to following dreams that my brain and heart knit together and I endlessly follow to personify those images. I love it more as I see many people walking on these routes these days and am positive that the scene will change.”