The opening sequence of Food Prints announces itself as an ‘epicurean voyage through Pakistan, an overview of Pakistani cuisine’. It tells the reader something of the ambition of the book. Fortunately for Ramzi she has managed to fulfill this ambition with a fair degree of success, although I cannot help but wonder whether this is because there is so little way of writing on Pakistan’s cuisine. A glance at the bibliography reinforces this view, as much of the reference material is around five years old. Having said that, as an avid reader of food literature I have often been frustrated by the lack of indigenous writing. Ramzi’s Food Prints marks what I hope is a beginning in the exploration of the diversity of Pakistani cuisine.

The book’s appeal lies in its structure. Its starting point is at history. Although sketchy, it sets the landscape for the multiple influences of civilizations, culture and peoples that compose Pakistani cuisine. Its strongest chapters are on cooking the Pakistani way and commonly used local ingredients. The descriptions of the techniques and the profile of spices along with their health properties make for an interesting read and resource for food writers. The author has consciously woven history into the narrative so that it becomes a central thread of the book.

At the heart of the book are the chapters detailing Pakistani cuisine along provincial, geographical and ethnic lines. Much of the detail here is familiar although there are points where the classification appears more rigid than the reality of the manner in which Pakistani’s eat. I can understand the author’s partiality and inclusion of Karachi. As Pakistan’s largest city and one that has experienced waves of migrants, it is only natural to dedicate a chapter to its cuisine. In fact the chapter cements this recognition through cataloging the rich culinary traditions of the Hyderabadis, Parsis, Bohras, Memons, Khojas and Lucknawis to mention a few. However the inclusion of cuisines such as Anglo-Indian, Dilliwallay and Chinese under Karachi alone are perplexing given their presence across the breadth of Pakistan.

And what of Pakistan’s cultural capital Lahore? Lahoris are as famed for their hearty appetites as they are for their long simmered nihari’s, tikka’s and leisurely Sunday brunches of halwa puri and channay. The city is a trendsetter for food-streets in both Islamabad and Karachi as it was the first to have one in Gawalmandi. Here one can find Punjabi specialities such as murghcholay, halva puri and siripaya alongside Kashmiri delicacies such as harissa and Kashmiri pink tea thick with cream and a sprinkle of pistachio.

These inconsistencies and shortcomings sit uneasily with the careful manner with which the author has researched the book. And carry through the concluding chapters of the book thatinclude recipes from around Pakistan. The structure and writing of the recipes leaves much to be desired. As a Pakistani living abroad I have often sought recipes for favourites such as channay or murghi ka salan only to find them of meagre assistance. Very little attention is paid to the role of heat, the sequence of the ingredient list and breaking the recipe into steps. I use the recipe ‘Burani’ to illustrate. To start with there is no prelude to the recipe. It would be helpful to include a short introduction to burani, essentially a cold yoghurt based dish that has come to Pakistan by way of Afghanistan and Iran. The instructions start thus – ‘Soak Eggplants; cut into thick round and fry till light brown’. Despite being a capable cook I am left wondering how the eggplants are to be soaked whole. For a novice, it is important to explain that soaking is necessary to extract the bitterness from the vegetable as well as prevent it from absorbing too much oil. Moving on, the recipe indicates one eighth of a cup of oil but does not say whether it is to be divided for frying the eggplants and onion separately, although both are to be fried. These oversights diminish the value of the recipes to those who would want to cook them.

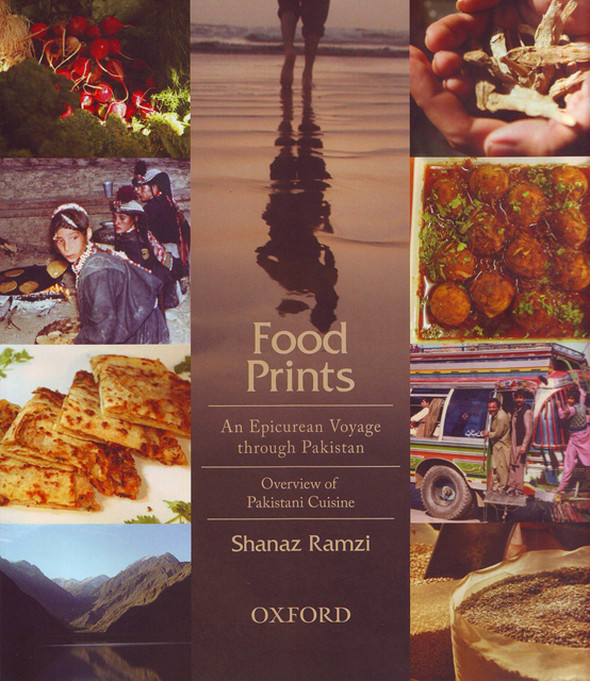

This review has not been easy to write because the strengths and the flaws of Food Prints are in equilibrium. The author’s love for Pakistani cuisine is without doubt, but her ambition to catalogue as much as possible leaves her unable to assume the fluidity with which cuisines have been adopted and adapted across Pakistan. Also, the design of the book as it appears through the cover, the glossy paper and photography is that of a coffee table edition however the contents and the density of the material indicate otherwise. Notwithstanding, it would be wrong to close without celebrating its strengths. Food Prints is a brave foray into Pakistani cuisine that is much loved at home and abroad but about which there is very little information. I do hope that Ramzi’s efforts will bring forth more food writing on and from Pakistan.